Palestine

Palestine (Greek: Παλαιστίνη, Palaistinē; Latin: Palaestina; the Hebrew name Peleshet (פלשת Pəléshseth); also פלשׂתינה, Palestina; Arabic: فلسطينFilasṭīn, Falasṭīn, Filisṭīn) is a conventional name used, among others, to describe a geographic region between the Mediterranean Sea and the Jordan River, and various adjoining lands.[1]

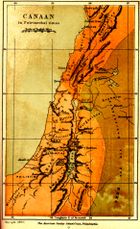

As a geographic term, Palestine can refer to "ancient Palestine," an area that today includes Israel and the Israeli-occupied[2] Palestinian territories, as well as part of Jordan, and some of both Lebanon and Syria.[1] In classical or contemporary terms, it is also the common name for the area west of the Jordan River. The boundaries of two new states were laid down within the territory of the British Mandate, Palestine and Transjordan.[3][4][5][6] Other terms for the same area include Canaan, Zion, the Land of Israel, and the Holy Land.

Origin of name

The name "Palestine" is the cognate of an ancient word meaning "Philistines" or "Land of the Philistines".[7][8][9] In keeping with the Greek culture of the day, it has also been suggested that it may also be a play on the word Παλαιστής Palaistes (Greek for wrestler) and a reference to Jacob, later called Israel, the founder of the ancient Israeli nation.[10]

The earliest known mention is thought to be in Ancient Egyptian texts of the temple at Medinet Habu which record a people called the P-r-s-t (conventionally Peleset) among the Sea Peoples who invaded Egypt in Ramesses III's reign.[11] The Hebrew name Peleshet (פלשת Pəléshseth)- usually translated as Philistia in English, is used in the Bible to denote the southern coastal region that was inhabited by the Philistines to the west of the ancient Kingdom of Judah.[12]

The Assyrian emperor Sargon II called the same region Palashtu or Pilistu in his Annals.[7][8][8][13] In the 5th century BCE, Herodotus wrote in Ancient Greek of a 'district of Syria, called Palaistinê" (whence Palaestina, whence Palestine).[7][14][15][16]

According to Moshe Sharon, Palaestina was commonly used to refer to the coastal region and shortly thereafter, the whole of the area inland to the west of the Jordan River.[7] The latter extension occurred when the Roman authorities, following the suppression of the Bar Kokhba rebellion in the 2nd century CE, renamed "Provincia Judea" (Iudaea Province; originally derived from the name "Judah") to "Syria Palaestina" (Syria Palaestina), in order to complete the dissociation with Judaea.[17][18]

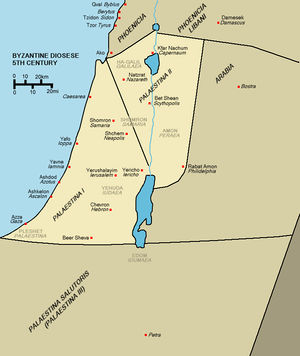

During the Byzantine period, the entire region (Syria Palestine, Samaria, and the Galilee) was named Palaestina, subdivided into provinces Palaestina I and II.[19] The Byzantines also renamed an area of land including the Negev, Sinai, and the west coast of the Arabian Peninsula as Palaestina Salutaris, sometimes called Palaestina III.[19]

The Arabic word for Palestine is Philistine (commonly transcribed in English as Filistin, Filastin, or Falastin).[20] Moshe Sharon writes that when the Arabs took over Greater Syria in the 7th century, place names that were in use by the Byzantine administration before them, generally continued to be used. Hence, he traces the emergence of the Arabic form Filastin to this adoption, with Arabic inflection, of Roman and Hebrew (Semitic) names.[7] Jacob Lassner and Selwyn Ilan Troen offer a different view, writing that Jund Filastin, the full name for the administrative province under the rule of the Arab caliphates, was traced by Muslim geographers back to the Philistines of the Bible.[21]

The use of the name "Palestine" in English became more common after the European renaissance.[22] The name was not used in Ottoman times (1517–1917). Most of Christian Europe referred to the area as the Holy Land. It was officially revived by the British after the fall of the Ottoman Empire and applied to the territory that was placed under British Mandate.

Some other terms that have been used to refer to all or part of this land include Canaan, Greater Israel, Greater Syria, the Holy Land, Iudaea Province, Judea,[23] Israel, "Israel HaShlema", Kingdom of Israel, Kingdom of Jerusalem, Land of Israel (Eretz Yisrael or Ha'aretz), Zion, Retenu (Ancient Egyptian), Southern Syria, and Syria Palestina.

Boundaries

The boundaries of Palestine have varied throughout history.[24][25] Prior to its being named Palestine, Ancient Egyptian texts (c. 14 century BCE) called the entire coastal area along the Mediterranean Sea between modern Egypt and Turkey R-t-n-u (conventionally Retjenu). Retjenu was subdivided into three regions and the southern region, Djahy, shared approximately the same boundaries as Canaan, or modern-day Israel and the Palestinian territories, though including also Syria.[26]

Scholars disagree as to whether the archaeological evidence supports the biblical story of there having been a Kingdom of Israel of the United Monarchy that reigned from Jerusalem, as the archaeological evidence is both rare and disputed.[27][28] For those who do interpret the archaeological evidence positively in this regard, it is thought to have ruled some time during Iron Age I (1200 - 1000 BCE) over an area approximating modern-day Israel and the Palestinian territories, extending farther westward and northward to cover much (but not all) of the greater Land of Israel.[27][28]

Philistia, the Philistine confederation, emerged circa 1185 BCE and comprised five city states: Gaza, Ashkelon, Ashdod on the coast and Ekron, and Gath inland.[13] Its northern border was the Yarkon River, the southern border extending to Wadi Gaza, its western border the Mediterranean Sea, with no fixed border to the east.[11]

By 722 BCE, Philistia had been subsumed by the Assyrian Empire, with the Philistines becoming 'part and parcel of the local population,' prospering under Assyrian rule during the 7th century despite occasional rebellions against their overlords.[13][29][30] In 604 BCE, when Assyrian troops commanded by the Babylonian empire carried off significant numbers of the population into slavery, the distinctly Philistine character of the coastal cities dwindled away, and the history of the Philistines as a distinct people effectively ended.[13][29][31]

The boundaries of the area and the ethnic nature of the people referred to by Herodotus in the 5th century BCE as Palaestina vary according to context. Sometimes, he uses it to refer to the coast north of Mount Carmel. Elsewhere, distinguishing the Syrians in Palestine from the Phoenicians, he refers to their land as extending down all the coast from Phoenicia to Egypt.[32] Josephus used the name Παλαιστινη only for the smaller coastal area, Philistia.[33] Pliny, writing in Latin in the 1st century CE, describes a region of Syria that was "formerly called Palaestina" among the areas of the Eastern Mediterranean.[34]

Since the Byzantine Period, the Byzantine borders of Palaestina (I and II, also known as Palaestina Prima, "First Palestine", and Palaestina Secunda, "Second Palestine"), have served as a name for the geographic area between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea. Under Arab rule, Filastin (or Jund Filastin) was used administratively to refer to what was under the Byzantines Palaestina Secunda (comprising Judaea and Samaria), while Palaestina Prima (comprising the Galilee region) was renamed Urdunn ("Jordan" or Jund al-Urdunn).[7]

The Zionist Organization provided their definition concerning the boundaries of Palestine in a statement to the Paris Peace Conference in 1919; it also includes a statement about the importance of water resources that the designated area includes.[35][36] On the basis of a League of Nations mandate, the British administered Palestine after World War I, promising to establish a Jewish homeland therein.[37] The original British Mandate included what is now Israel, the West Bank (of the Jordan), and trans-Jordan (the present kingdom of Jordan),although the latter was disattached by an administrative decision of the British in 1922.[38] To the Palestinian people who view Palestine as their homeland, its boundaries are those of the British Mandate excluding the Transjordan, as described in the Palestinian National Charter.[39]

Additional extrabiblical references

An archaeological textual reference concerning the territory of Palestine is thought to have been made in the Merneptah Stele, dated c. 1200 BCE, containing a recount of Egyptian king Merneptah's victories in the land of Canaan, mentioning place-names such as Gezer, Ashkelon and Yanoam, along with Israel, which is mentioned using a hieroglyphic determinative that indicates a nomad people, rather than a state.[40]

.jpg)

Another famous inscription is that of the Mesha Stele, bearing an inscription by the 9th century BC Moabite King Mesha, discovered in 1868 at Dhiban (biblical "Dibon," capital of Moab) now in Jordan. The Stele is notable because it is thought to be the earliest known reference to the sacred Hebrew name of God – YHWH. It also notable as the most extensive inscription ever recovered that refers to ancient Israel.

Biblical texts

In the Biblical account, the United Kingdom of Israel and Judah ruled from Jerusalem a vast territory extending far west and north of Palestine for some 120 years. Archaeological evidence for this period is very rare, however, and its implications much disputed.[27][28]

The Hebrew Bible calls the region Canaan (כּנען) (Numbers 34:1–12), while the part of it occupied by Israelites is designated Israel (Yisrael). The name "Land of the Hebrews" (ארץ העברים, Eretz Ha-Ivrim) is also found, as well as several poetical names: "land flowing with milk and honey", "land that [God] swore to your fathers to assign to you", "Land of the Lord", and the "Promised Land".

The Land of Canaan is given a precise description in (Numbers 34:1) as including all of Lebanon, as well (Joshua 13:5). The wide area appears to have been the home of several small nations such as the Canaanites, Hebrews, Hittites, Amorrhites, Pherezites, Hevites and Jebusites. According to Hebrew tradition, the land of Canaan is part of the land given to the descendants of Abraham, which extends from the "river of Egypt" to the Euphrates River (Genesis 15:18) – some identify the river of Egypt with the Nile, others believe it to be a wadi in northern Sinai, cf. Numbers 34:5; Joshua 15:3-4; Joshua 15:47; 1 Kings 8:65; 2 Kings 24:7.

In Exodus 13:17, "And it came to pass, when Pharaoh had let the people go, that God led them not through the way of the land of the Philistines, although that was near; for God said, Lest peradventure the people repent when they see war, and they return to Egypt."

The events of the Four Gospels of the Christian Bible take place almost entirely in this country, which in Christian tradition thereafter became known as The Holy Land.

In the Qur'an, the term الأرض المقدسة (Al-Ard Al-Muqaddasah, English: "Holy Land") is mentioned at least seven times, once when Moses proclaims to the Children of Israel: "O my people! Enter the holy land which Allah hath assigned unto you, and turn not back ignominiously, for then will ye be overthrown, to your own ruin." (Surah 5:21)

History

Paleolithic and Neolithic periods (1 mya–5000 BCE)

The earliest human remains in Palestine were found in Ubeidiya, some 3 km south of the Sea of Galilee (Lake Tiberias), in the Jordan Rift Valley. The remains are dated to the Pleistocene, ca. 1.5 million years ago. It is traces of the earliest migration of Homo erectus out of Africa. The site yielded hand axes of the Acheulean type.[41]

Wadi El Amud between Safed and the Sea of Galilee was the site of the first prehistoric digging in Palestine, in 1925. The discovery of the Palestine Man in the Zuttiyeh Cave in Wadi Al-Amud near Safed in 1925 provided some clues to human development in the area.[42][43]

Qafzeh is a paleoanthropological site south of Nazareth where eleven significant fossilised Homo sapiens skeletons have been found at the main rock shelter. These anatomically modern humans, both adult and infant, are now dated to circa 90–100,000 years old, and many of the bones are stained with red ochre which is conjectured to have been used in the burial process, a significant indicator of ritual behavior and thereby symbolic thought and intelligence. 71 pieces of unused red ochre also littered the site.

Mount Carmel has yielded several important findings, among them Kebara Cave that was inhabited between 60,000 – 48,000 BP and where the most complete Neanderthal skeleton found to date. The Tabun cave was occupied intermittently during the Lower and Middle Paleolithic ages (500,000 to around 40,000 years ago). Excavation suggests that it features one of the longest sequences of human occupation in the Levant. In the nearby Es Skhul cave excavations revealed the first evidence of the late Epipalaeolithic Natufian culture, characterized by the presence of abundant microliths, human burials and ground stone tools. This also represents one area where Neanderthals – present in the region from 200,000 to 45,000 years ago – lived alongside modern humans dating to 100,000 years ago.[44]

In the caves of Shuqba in Ramallah and Wadi Khareitun in Bethlehem, stone, wood and animal bone tools were found and attributed to the Natufian culture (c. 12800–10300 BCE). Other remains from this era have been found at Tel Abu Hureura, Ein Mallaha, Beidha and Jericho.[45]

Between 10000 and 5000 BCE, agricultural communities were established. Evidence of such settlements were found at Tel es-Sultan in Jericho and consisted of a number of walls, a religious shrine, and a 23-foot (7.0 m) tower with an internal staircase[46][47] Jericho is believed to be one of the oldest continuously-inhabited cities in the world, with evidence of settlement dating back to 9000 BC, providing important information about early human habitation in the Near East.[48]

Chalcolithic period (4500–3000 BCE) and Bronze Age (3000–1200 BCE)

Along the Jericho–Dead Sea–Bir es-Saba–Gaza–Sinai route, a culture originating in Syria, marked by the use of copper and stone tools, brought new migrant groups to the region contributing to an increasingly urban fabric.[49][50][51]

By the early Bronze Age (3000–2200 BCE) independent Canaanite city-states situated in plains and coastal regions and surrounded by mud-brick defensive walls were established and most of these cities relied on nearby agricultural hamlets for their food needs.[49][52]

Archaeological finds from the early Canaanite era have been found at Tel Megiddo, Jericho, Tel al-Far'a (Gaza), Bisan, and Ai (Deir Dibwan/Ramallah District), Tel an Nasbe (al-Bireh) and Jib (Jerusalem).

The Canaanite city-states held trade and diplomatic relations with Egypt and Syria. Parts of the Canaanite urban civilization were destroyed around 2300 BCE, though there is no consensus as to why. Incursions by nomads from the east of the Jordan River who settled in the hills followed soon thereafter.[49][53]

In the Middle Bronze Age (2200–1500 BCE), Canaan was influenced by the surrounding civilizations of ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, Phoenicia, Minoan Crete, and Syria. Diverse commercial ties and an agriculturally based economy led to the development of new pottery forms, the cultivation of grapes, and the extensive use of bronze.[49][54] Burial customs from this time seemed to be influenced by a belief in the afterlife.[49][55]

Political, commercial and military events during the Late Bronze Age period (1450–1350 BCE) were recorded by ambassadors and Canaanite proxy rulers for Egypt in 379 cuneiform tablets known as the Amarna Letters.[56] The Minoan influence is apparent at Tel Kabri.[57]

By c. 1190 BCE, the Philistines arrived and mingled with the local population, losing their separate identity over several generations.[29][58]

Iron Age (1200–330 BCE)

Pottery remains found in Ashkelon, Ashdod, Gath (city), Ekron and Gaza decorated with stylized birds provided the first archaeological evidence for Philistine settlement in the region. The Philistines are credited with introducing iron weapons and chariots to the local population.[59] Excavations have established that the late 13th, the 12th and the early 11th centuries BCE witnessed the foundation of perhaps hundreds of insignificant, unprotected village settlements, many in the mountains of Palestine.[60] From around the 11th century BCE, there was a reduction in the number of villages, though this was counterbalanced by the rise of certain settlements to the status of fortified townships.[60]

Developments in Palestine between 1250 and 900 BCE have been the focus of debate between those who accept the Old Testament version on the conquest of Canaan by the Israelite tribes, and those who reject it.[61] Niels Peter Lemche, of the Copenhagen School of Biblical Studies, submits that the picture of ancient Israel "is contrary to any image of ancient Palestinian society that can be established on the basis of ancient sources from Palestine or referring to Palestine and that there is no way this image in the Bible can be reconciled with the historical past of the region."[60]

Sites and artifacts, including the Large Stone Structure, Mount Ebal, the Menertaph, and Mesha stelae, among others, are subject to widely varying historical interpretations: the "conservative camp" reconstructs the history of Israel according to the biblical text and views archaeological evidence in that context, whilst scholars in the minimalist or deconstructionist school hold that there is no archaeological evidence supporting the idea of a United Monarchy (or Israelite nation) and the biblical account is a religious mythology created by Judean scribes in the Persian and Hellenistic periods; a third camp of centrist scholars acknowledges the value of some isolated elements of the Pentateuch and of Deuteronomonistic accounts as potentially valid history of monarchic times that can be in accord with the archaeological evidence, but argue that nevertheless the biblical narrative should be understood as highly ideological and adapted to the needs of the community at the time of its compilation.[62][63][64][65][66][67]

Hebrew Bible/Old Testament period

According to Biblical tradition, the United Kingdom of Israel was established by the Israelite tribes with Saul as its first king in 1020 BCE.[68] In 1000 BCE, Jerusalem was made the capital of King David's kingdom and it is believed that the First Temple was constructed in this period by King Solomon.[68] By 930 BCE, the united kingdom split to form the northern Kingdom of Israel, and the southern Kingdom of Judah.[68] These kingdoms co-existed with several more kingdoms in the greater Palestine area, including Philistine town states on the Southwestern Mediterranean coast, Edom, to the South of Judah, and Moab and Ammon to the East of the river Jordan.[69] According to Jon Schiller and Hermann Austel, among others, while in the past, the Bible story was seen historical truth, "a growing number of archaeological scholars, particularly those of the minimalist school, are now insisting that Kings David and Solomon are 'no more real than King Arthur,' citing the lack of archaeological evidence attesting to the existence of the United Kingdom of Israel, and the unreliability of biblical texts, due to their being composed in a much later period."[70][71]

There was an at least partial Egyptian withdrawal from Palestine in this period, though it is likely that Bet Shean was an Egyptian garrison as late as the beginning of the 10th century BCE.[60] The socio-political system was characterized by local patrons fighting other local patrons, lasting until around the mid-9th century BCE when some local chieftains were able to create large political structures that exceeded the boundaries of those present in the Late Bronze Age Levant.[60]

Archaeological findings from this era include, among others, the Mesha Stele, from c. 850 BCE, which recounts the conquering of Moab, located East of the Dead Sea, by king Omri, and the successful revolt of Moabian king Mesha against Omri's son, presumably King Ahab (and French scholar André Lemaire reported that line 31 of the Stele bears the phrase "the house of David" (in Biblical Archaeology Review [May/June 1994], pp. 30–37).[72]); and the Kurkh Monolith, dated c. 835 BCE, describing King Shalmaneser III of Assyria's Battle of Qarqar, where he fought alongside the contingents of several kings, among them King Ahab and King Gindibu.

Between 722 and 720 BCE, the northern Kingdom of Israel was destroyed by the Assyrian Empire and the Israelite tribes – thereafter known as the Lost Tribes – were exiled.[68] The most important finding from the southern Kingdom of Judah is the Siloam Inscription, dated c. 700 BCE, which celebrates the successful encounter of diggers, digging from both sides of the Jerusalem wall to create the Hezekiah water tunnel and water pool, mentioned in the Bible, in 2Kings 20:20.[73][74][75][76] In 586 BCE, Judah was conquered by the Babylonians and Jerusalem and the First Temple destroyed.[68] Most of the surviving Jews, and much of the other local population, were deported to Babylonia.[29][77]

Persian rule (538 BCE)

After the Persian Empire was established, Jews were allowed to return to what their holy books had termed the Land of Israel, and having been granted some autonomy by the Persian administration, it was during this period that the Second Temple in Jerusalem was built.[29][78] Sebastia, near Nablus, was the northernmost province of the Persian administration in Palestine, and its southern borders were drawn at Hebron.[29][79] Some of the local population served as soldiers and lay people in the Persian administration, while others continued to agriculture. In 400 BCE, the Nabataeans made inroads into southern Palestine and built a separate civilization in the Negev that lasted until 160 BCE.[29][80]

Classical antiquity

Hellenistic rule (333 BCE)

The Persian Empire fell to Greek forces of the Macedonian general Alexander the Great.[81][82] After his death, with the absence of heirs, his conquests were divided amongst his generals, while the region of the Jews ("Judah" or Judea as it became known) was first part of the Ptolemaic dynasty and then part of the Seleucid Empire.[83]

The landscape during this period was markedly changed by extensive growth and development that included urban planning and the establishment of well-built fortified cities.[79][81] Hellenistic pottery was produced that absorbed Philistine traditions. Trade and commerce flourished, particularly in the most Hellenized areas, such as Ashkelon, Jaffa,[84] Jerusalem,[85] Gaza,[86] and ancient Nablus (Tell Balatah).[81][87]

The Jewish population in Judea was allowed limited autonomy in religion and administration.[88]

Hasmonean dynasty (140 BCE)

An independent Jewish kingdom under the Hasmonean Dynasty existed from 140–37 BCE. In the 2nd century BCE fascination in Jerusalem for Greek culture resulted in a movement to break down the separation of Jew and Gentile and some people even tried to disguise the marks of their circumcision.[89] Disputes between the leaders of the reform movement, Jason and Menelaus, eventually led to civil war and the intervention of Antiochus IV Epiphanes.[89] Subsequent persecution of the Jews led to the Maccabean Revolt under the leadership of the Hasmoneans, and the construction of a native Jewish kingship under the Hasmonean Dynasty.[89] After approximately a century of independence disputes between the Hasmonean rivals Aristobulus and Hyrcanus led to control of the kingdom by the Roman army of Pompey. The territory then became first a Roman client kingdom under Hyrcanus and then, in 70CE, a Roman Province administered by the governor of Syria.[90]

Roman rule (63 BCE)

Though General Pompey arrived in 63 BCE, Roman rule was solidified when Herod, whose dynasty was of Idumean ancestry, was appointed as king.[81][91] Urban planning under the Romans was characterized by cities designed around the Forum – the central intersection of two main streets – the Cardo, running north-south and the Decumanus running east-west.[92] Cities were connected by an extensive road network developed for economic and military purposes. Among the most notable archaeological remnants from this era are Herodium (Tel al-Fureidis) to the south of Bethlehem,[93] Masada and Caesarea Maritima.[81][94] Herod arranged a renovation of the Second Temple in Jerusalem, with a massive expansion of the Temple Mount platform and major expansion of the Jewish Temple around 19 BCE. The Temple Mount's natural plateau was extended by enclosing the area with four massive retaining walls and filling the voids. This artificial expansion resulted in a large flat expanse which today forms the eastern section of the Old City of Jerusalem.

Around the time associated with the birth of Jesus, Roman Palestine was in a state of disarray and direct Roman rule was re-established.[81][95] The early Christians were oppressed and while most inhabitants became Romanized, others, particularly Jews, found Roman rule to be unbearable.[81][95]

As a result of the First Jewish-Roman War (66–73), Titus sacked Jerusalem destroying the Second Temple, leaving only supporting walls, including the Western Wall.

In 135, following the fall of a Jewish revolt led by Bar Kokhba in 132–135, the Roman emperor Hadrian attempted the expulsion of Jews from Judea. His attempt was as unsuccessful as were most of Rome's many attempts to alter the demography of the Empire; this is demonstrated by the continued existence of the rabbinical academy of Lydda in Judea, and in any case large Jewish populations remained in Samaria and the Galilee.[17] Tiberias became the headquarters of exiled Jewish patriarchs. The Romans joined the province of Judea (which already included Samaria) together with Galilee to form a new province, called Syria Palaestina, to complete the disassociation with Judaea.[17] Notwithstanding the oppression, some two hundred Jewish communities remained. Gradually, certain religious freedoms were restored to the Jewish population, such as exemption from the imperial cult and internal self-administration. The Romans made no such concession to the Samaritans, to whom religious liberties were denied, while their sanctuary on Mt.Gerizim was defiled by a pagan temple, as part of measures were taken to suppress the resurgence of Samaritan nationalism.[17]

In 132 CE, the Emperor Hadrian changed the name of the province from Iudaea to Syria Palaestina and renamed Jerusalem "Aelia Capitolina" and built temples there to honor Jupiter. Christianity was practiced in secret and the Hellenization of Palestine continued under Septimius Severus (193–211 CE).[81] New pagan cities were founded in Judea at Eleutheropolis (Bayt Jibrin), Diopolis (Lydd), and Nicopolis (Emmaus).[79][81]

Byzantine (Eastern Roman) rule (330–640 CE)

Emperor Constantine I's conversion to Christianity around 330 CE made Christianity the official religion of Palaestina.[96][97] After his mother Empress Helena identified the spot she believed to be where Christ was crucified, the Church of the Holy Sepulcher was built in Jerusalem.[96] The Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem and the Church of the Ascension in Jerusalem were also built during Constantine's reign.[96] This was the period of its greatest prosperity in antiquity. Urbanization increased, large new areas were put under cultivation, monasteries proliferated, synagogues were restored, and the population West of the Jordan may have reached as many as one million.[17]

Palestine thus became a center for pilgrims and ascetic life for men and women from all over the world.[79][96] Many monasteries were built including the St. George's Monastery in Wadi al-Qelt, the Monastery of the Temptation and Deir Hajla near Jericho, and Deir Mar Saba and Deir Theodosius east of Bethlehem.[96]

In 351-352, a Jewish revolt against Byzantine rule in Tiberias and other parts of the Galilee was brutally suppressed. Imperial patronage for Christian cults and immigration was strong, and a significant wave of immigration from Rome, especially to the area about Aelia Capitolina and Bethlehem, took place after that city was sacked in 410.[17]

In approximately 390 CE, Palaestina was further organised into three units: Palaestina Prima, Secunda, and Tertia (First, Second, and Third Palestine), part of the Diocese of the East.[98][96] Palaestina Prima consisted of Judea, Samaria, the coast, and Peraea with the governor residing in Caesarea. Palaestina Secunda consisted of the Galilee, the lower Jezreel Valley, the regions east of Galilee, and the western part of the former Decapolis with the seat of government at Scythopolis. Palaestina Tertia included the Negev, southern Jordan—once part of Arabia—and most of Sinai with Petra as the usual residence of the governor. Palestina Tertia was also known as Palaestina Salutaris.[96][99]

In 536 CE, Justinian I promoted the governor at Caesarea to proconsul (anthypatos), giving him authority over the two remaining consulars. Justinian believed that the elevation of the governor was appropriate because he was responsible for "the province in which our Lord Jesus Christ... appeared on earth".[100] This was also the principal factor explaining why Palestine prospered under the Christian Empire. The cities of Palestine, such as Caesarea Maritima, Jerusalem, Scythopolis, Neapolis, and Gaza reached their peak population in the late Roman period and produced notable Christian scholars in the disciplines of rhetoric, historiography, Eusebian ecclesiastical history, classicizing history and hagiography.[100]

Byzantine administration of Palestine was temporarily suspended during the Persian occupation of 614–28, and then permanently after the Muslims arrived in 634 CE, defeating the empire's forces decisively at the Battle of Yarmouk in 636 CE. Jerusalem capitulated in 638 CE and Caesarea between 640 CE and 642 CE.[100]

Islamic period (630–1918 CE)

The Islamic prophet Muhammad established a new unified political polity in the Arabian peninsula at the beginning of the 7th century. The subsequent Rashidun and Umayyad Caliphates saw a century of rapid expansion of Arab power well beyond the Arabian peninsula in the form of a vast Muslim Arab Empire. In the 630s this empire conquered Palestine and it remained under the control of Islamic Empires for most of the next 1300 years.

Arab Caliphate rule (638–1099 CE)

In 638 CE, following the Siege of Jerusalem, the Caliph Omar Ibn al-Khattab and Safforonius, the Patriarch of Jerusalem, signed Al-Uhda al-'Omariyya (The Umariyya Covenant), an agreement that stipulated the rights and obligations of all non-Muslims in Palestine.[96] Christians and Jews where considered People of the Book, enjoyed some protection but had to pay a special poll tax called jizyah ("tribute"). During the early years of Muslim control of the city, a small permanent Jewish population returned to Jerusalem after a 500-year absence.[101]

Omar Ibn al-Khattab was the first conqueror of Jerusalem to enter the city on foot, and when visiting the site that now houses the Haram al-Sharif, he declared it a sacred place of prayer.[102][103] Cities that accepted the new rulers, as recorded in registrars from the time, were: Jerusalem, Nablus, Jenin, Acre, Tiberias, Bisan, Caesarea, Lajjun, Lydd, Jaffa, Imwas, Beit Jibrin, Gaza, Rafah, Hebron, Yubna, Haifa, Safed and Ashkelon.[104]

Umayyad rule (661–750 CE)

Under Umayyad rule, the Byzantine province of Palaestina Prima became the administrative and military sub-province (jund) of Filastin – the Arabic name for Palestine from that point forward.[105] It formed part of the larger province of ash-Sham (Arabic for Greater Syria).[106] Jund Filastin (Arabic جند فلسطين, literally "the army of Palestine") was a region extending from the Sinai to the plain of Acre. Major towns included Rafah, Caesarea, Gaza, Jaffa, Nablus and Jericho.[107] Lod served as the headquarters of the province of Filastin and the capital later moved to Ramla. Jund al-Urdunn (literally "the army of Jordan") was a region to the north and east of Filastin which included the cities of Acre, Bisan and Tiberias.[107]

In 691, Caliph Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan ordered that the Dome of the Rock be built on the site where the Islamic prophet Muhammad is believed by Muslims to have begun his nocturnal journey to heaven, on the Temple Mount. About a decade afterward, Caliph Al-Walid I had the Al-Aqsa Mosque built.[108]

It was under Umayyad rule that Christians and Jews were granted the official title of "Peoples of the Book" to underline the common monotheistic roots they shared with Islam.[104][109]

Abbasid rule (750–969 CE)

The Baghdad-based Abbasid Caliphs renovated and visited the holy shrines and sanctuaries in Jerusalem[110] and continued to build up Ramle.[104][111] Coastal areas were fortified and developed and port cities like Acre, Haifa, Caesarea, Arsuf, Jaffa and Ashkelon received monies from the state treasury.[112]

A trade fair took place in Jerusalem every year on September 15 where merchants from Pisa, Genoa, Venice and Marseilles converged to acquire spices, soaps, silks, olive oil, sugar and glassware in exchange for European products.[112] European Christian pilgrims visited and made generous donations to Christian holy places in Jerusalem and Bethlehem.[112] During Harun al-Rashid's (786–809) reign the first contacts with the Frankish Kingdom of Charlemagne occurred, though the actual extent of these contacts is not known. As a result, Charlemagne sent money for construction of churches and a Latin Pilgrims' Inn in Jerusalem.[113] The establishment of the Pilgrims' Inn in Jerusalem is seen as a fulfillment of Umar's pledge to Bishop Sophronious to allow freedom of religion and access to Jerusalem for Christian pilgrims.[114]

The influence of the Arab tribes declined and the only context where they are reported is in uprising against the central authority.[115] I 796, a civil war between the Mudhar and Yamani tribes occurred, resulting in widespread destruction in Palestine.[116] The Abbasids visited the country less frequently than the Ummayads, but ordered some significant constructions in Jerusalem. Thus, Al-Mansur Ordered in 758 the renovation of the Dome of the Rock that had collapsed in an earthquake.[117]

Fatimid rule (969–1099 CE)

From their base in Tunisia, the Shi'ite Fatimids, who claimed to be descendants of Muhammad through his daughter Fatimah, conquered Palestine by way of Egypt in 969 CE.[118] Their capital was Cairo. Jerusalem, Nablus, and Askalan were expanded and renovated under their rule.[112]

After the 10th century, the division into Junds began to break down.[112] In the second half of the 11th Century the Fatimids empire suffered setback from fighting with the Seljuk Turks. Warfare between the Fatimids and Seljuks caused great disruption for the local Christians and for western pilgrims. The Fatimids had lost Jerusalem to the Seljuks in 1073,[119] but recaptured it from the Ortoqids, a smaller Turkic tribe associated with the Seljuks, in 1098, just before the arrival of the crusaders.[120]

- See also the Mideastweb map of "Palestine Under the Caliphs", showing Jund boundaries (external link).

Crusader rule (1099–1187 CE)

The Kingdom of Jerusalem was a Christian kingdom established in the Levant in 1099 after the First Crusade. It lasted nearly two hundred years, from 1099 until 1291 when the last remaining possession, Acre, was destroyed by the Mamluks.

At first the kingdom was little more than a loose collection of towns and cities captured during the crusade. At its height, the kingdom roughly encompassed the territory of modern-day Israel and the Palestinian territories. It extended from modern Lebanon in the north to the Sinai Desert in the south, and into modern Jordan and Syria in the east. There were also attempts to expand the kingdom into Fatimid Egypt. Its kings also held a certain amount of authority over the other crusader states, Tripoli, Antioch, and Edessa.

Many customs and institutions were imported from the territories of Western Europe from which the crusaders came, and there were close familial and political connections with the West throughout the kingdom's existence. It was, however, a relatively minor kingdom in comparison and often lacked financial and military support from Europe. The kingdom had closer ties to the neighbouring Kingdom of Armenia and the Byzantine Empire, from which it inherited "oriental" qualities, and the kingdom was also influenced by pre-existing Muslim institutions. Socially, however, the "Latin" inhabitants from Western Europe had almost no contact with the Muslims and native Christians whom they ruled.

Under the European rule, fortifications, castles, towers and fortified villages were built, rebuilt and renovated across Palestine largely in rural areas.[112][121] A notable urban remnant of the Crusader architecture of this era is found in Acre's old city.[112][122]

During the period of Crusader control, it has been estimated that Palestine had only 1,000 poor Jewish families.[123] Jews fought alongside the Muslims in Jerusalem in 1099 and Haifa in 1100 against the Crusaders. They were not allowed to live in Jerusalem and initially most of cities saw the destruction of the Jewish communities, but communities did continue in the rural areas. For instance, it is known about at least 24 villages in the Galilee were Jews lived. Later in the history of the Crusaders state Jews settled in the Coastal cities. Unlike the treatment of Jews by the Crusaders Europe, where many Massacres occurred, in Palestine no distinction was made between Jews and other non Christians and there were no laws specifically against Jews. Some Jews from Europe visited the country, like Benjamin of Tudela who wrote about it.[124] Maimonides escaped to Palestine from the Almohads in 1165 and visited Acre, Jerusalem and Hebron, finally settling in Fostat in Egypt.[125]

In July 1187, the Cairo-based Kurdish General Saladin commanded his troops to victory in the Battle of Hattin.[126][127] Saladin went on to take Jerusalem. An agreement granting special status to the Crusaders allowed them to continue to stay in Palestine and In 1229, Frederick II negotiated a 10-year treaty that placed Jerusalem, Nazareth and Bethlehem once again under Crusader rule.[126]

In 1270, Sultan Baibars expelled the Crusaders from most of the country, though they maintained a base at Acre until 1291.[126] Thereafter, any remaining Europeans either went home or merged with the local population.[127]

Mamluk rule (1270–1516 CE)

Palestine formed a part of the Damascus Wilayah (district) under the rule of the Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt and was divided into three smaller Sanjaks (subdivisions) with capitals in Jerusalem, Gaza, and Safed.[127] Celebrated by Arab and Muslim writers of the time as the "blessed land of the Prophets and Islam's revered leaders,"[127] Muslim sanctuaries were "rediscovered" and received many pilgrims.[128]

During the end of the 13th century the Mamluks fought against the Mongols, and a decisive battle took place in Ain Jalut in the Jezreel Valley on 3 September 1260. The Mamluks achieved a decisive victory, and the battle established a highwater mark for the Mongol conquests.

The Mamluks, continuing the policy of the Ayyubids, made the strategic decision to destroy the coastal area and to bring desolation to many of its cities, from Tyre in the north to Gaza in the south. Ports were destroyed and various materials were dumped to make them inoperable. The goal was to prevent attacks from the sea, given the fear of the return of the crusaders. This had a long term affect on those areas, that remained sparsely populated for centuries. In Jerusalem, the walls, gates and fortifications were destroyed as well, for similar reasons. The activity in that time concentrated more inland.[129] The Mamluks constructed a "postal road" from Cairo to Damascus, that included lodgings for travelers (khans) and bridges, some of which survive to this day (Jisr Jindas, near Lod). The also saw the construction of many schools and the renovation of mosques neglected or destroyed during the Crusader period.[128]

In 1267 the Catalan Rabbi Nahmanides left Europe, seeking refuge in Muslim lands from Christian persecution,[130] he made aliyah to Jerusalem. There he established a synagogue in the Old City that exists until present day, known as the Ramban Synagogue and re-established Jewish communal life in Jerusalem.

In 1486, hostilities broke out between the Mamluks and the Ottoman Turks in a battle for control over western Asia. The Mamluk armies were eventually defeated by the forces of the Ottoman Sultan, Selim I, and lost control of Palestine after the 1516 battle of Marj Dabiq.[127][131]

Ottoman rule (1516–1831 CE)

After the Ottoman conquest, the name "Palestine" disappeared as the official name of an administrative unit, as the Turks often called their (sub)provinces after the capital. Following its 1516 incorporation in the Ottoman Empire, it was part of the vilayet (province) of Damascus-Syria until 1660. It then became part of the vilayet of Saida (Sidon), briefly interrupted by the 7 March 1799 – July 1799 French occupation of Jaffa, Haifa, and Caesarea. During the Siege of Acre in 1799, Napoleon prepared a proclamation declaring a Jewish state in Palestine.

Egyptian rule (1831–1841)

On 10 May 1832 the territories of Bilad ash-Sham, which include modern Syria, Jordan, Lebanon, and Palestine were conquered and annexed by Muhammad Ali's expansionist Egypt (nominally still Ottoman) in the 1831 Egyptian-Ottoman War. Britain sent the navy to shell Beirut and an Anglo-Ottoman expeditionary force landed, causing local uprisings against the Egyptian occupiers. A British naval squadron anchored off Alexandria. The Egyptian army retreated to Egypt. Muhammad Ali signed the Treaty of 1841. Britain returned control of the Levant to the Ottomans.

Ottoman rule (1841–1917)

In the reorganisation of 1873, which established the administrative boundaries that remained in place until 1914, Palestine was split between three major administrative units. The northern part, above a line connecting Jaffa to north Jericho and the Jordan, was assigned to the vilayet of Beirut, subdivided into the sanjaks (districts) of Acre, Beirut and Nablus. The southern part, from Jaffa downwards, was part of the special district of Jerusalem. Its southern boundaries were unclear but petered out in the eastern Sinai Peninsula and northern Negev Desert. Most of the central and southern Negev was assigned to the wilayet of Hijaz, which also included the Sinai Peninsula and the western part of Arabia.[132]

Nonetheless, the old name remained in popular and semi-official use. Many examples of its usage in the 16th and 17th centuries have survived.[133] During the 19th century, the Ottoman Government employed the term Ardh-u Filistin (the 'Land of Palestine') in official correspondence, meaning for all intents and purposes the area to the west of the River Jordan which became 'Palestine' under the British in 1922.[134] However, the Ottomans regarded "Palestine" as an abstract description of a general region but not as a specific administrative unit with clearly defined borders. This meant that they did not consistently apply the name to a clearly defined area.[132] Ottoman court records, for instance, used the term to describe a geographical area that did not include the sanjaks of Jerusalem, Hebron and Nablus, although these had certainly been part of historical Palestine.[135][136] Amongst the educated Arab public, Filastin was a common concept, referring either to the whole of Palestine or to the Jerusalem sanjak alone[137] or just to the area around Ramle.[138]

The end of the 19th century saw the beginning of Zionist immigration. The "First Aliyah" was the first modern widespread wave of Zionist aliyah. Jews who migrated to Palestine in this wave came mostly from Eastern Europe and from Yemen. This wave of aliyah began in 1881–82 and lasted until 1903.[139] An estimated 25,000[140]–35,000[141] Jews immigrated during the First Aliyah. The First Aliyah laid the cornerstone for Jewish settlement in Israel and created several settlements such as Rishon LeZion, Rosh Pina, Zikhron Ya'aqov and Gedera.

The "Second Aliyah" took place between 1904 and 1914, during which approximately 40,000 Jews immigrated, mostly from Russia and Poland,[142] and some from Yemen. The Second Aliyah immigrants were primarily idealists, inspired by the revolutionary ideals then sweeping the Russian Empire who sought to create a communal agricultural settlement system in Palestine. They thus founded the kibbutz movement. The first kibbutz, Degania, was founded in 1909. Tel Aviv was founded at that time, though its founders were not necessarily from the new immigrants. The Second Aliyah is largely credited with the Revival of the Hebrew language and establishing it as the standard language for Jews in Israel. Eliezer Ben-Yehuda contributed to the creation of the first modern Hebrew dictionary. Although he was an immigrant of the First Aliyah, his work mostly bore fruit during the second.

Ottoman rule over the eastern Mediterranean lasted until World War I when the Ottomans sided with the German Empire and the Central Powers. During World War I, the Ottomans were driven from much of the region by the British Empire during the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire.

20th century

In common usage up to World War I, "Palestine" was used either to describe the Consular jurisdictions of the Western Powers[143] or for a region that extended in the north-south direction typically from Rafah (south-east of Gaza) to the Litani River (now in Lebanon). The western boundary was the sea, and the eastern boundary was the poorly-defined place where the Syrian desert began. In various European sources, the eastern boundary was placed anywhere from the Jordan River to slightly east of Amman. The Negev Desert was not included.[144]

For 400 years foreigners enjoyed extraterritorial rights under the terms of the Capitulations of the Ottoman Empire. One American diplomat wrote that "Extraordinary privileges and immunities had become so embodied in successive treaties between the great Christian Powers and the Sublime Porte that for most intents and purposes many nationalities in the Ottoman empire formed a state within the state".[145]

The Consuls were originally magistrates who tried cases involving their own citizens in foreign territories. While the jurisdictions in the secular states of Europe had become territorial, the Ottomans perpetuated the legal system they inherited from the Byzantine Empire. The law in many matters was personal, not territorial, and the individual citizen carried his nation's law with him wherever he went.[146] Capitulatory law applied to foreigners in Palestine. Only Consular Courts of the State of the foreigners concerned were competent to try them. That was true, not only in cases involving personal status, but also in criminal and commercial matters.[147]

According to American Ambassador Morgenthau, Turkey had never been an independent sovereignty.[148] The Western Powers had their own courts, marshals, colonies, schools, postal systems, religious institutions, and prisons. The Consuls also extended protections to large communities of Jewish protégés who had settled in Palestine.[149]

The Moslem, Christian, and Jewish communities of Palestine were allowed to exercise jurisdiction over their own members according to charters granted to them. For centuries the Jews and Christians had enjoyed a large degree of communal autonomy in matters of worship, jurisdiction over personal status, taxes, and in managing their schools and charitable institutions. In the 19th century those rights were formally recognized as part of the Tanzimat reforms and when the communities were placed under the protection of European public law.[150][151]

Under the Sykes–Picot Agreement of 1916, it was envisioned that most of Palestine, when freed from Ottoman control, would become an international zone not under direct French or British colonial control. Shortly thereafter, British foreign minister Arthur Balfour issued the Balfour Declaration of 1917, which promised to establish a Jewish national home in Palestine.[152]

The British-led Egyptian Expeditionary Force, commanded by Edmund Allenby, captured Jerusalem on 9 December 1917 and occupied the whole of the Levant following the defeat of Turkish forces in Palestine at the Battle of Megiddo in September 1918 and the capitulation of Turkey on 31 October.[153]

British Mandate (1920–1948)

Following the First World War and the occupation of the region by the British, the principal Allied and associated powers drafted the Mandate which was formally approved by the League of Nations in 1922. Great Britain administered Palestine on behalf of the League of Nations between 1920 and 1948, a period referred to as the "British Mandate." Two states were established within the boundaries of the Mandate territory, Palestine and Transjordan.[154][155] - The preamble of the mandate declared:

"Whereas the Principal Allied Powers have also agreed that the Mandatory should be responsible for putting into effect the declaration originally made on November 2nd, 1917, by the Government of His Britannic Majesty, and adopted by the said Powers, in favor of the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, it being clearly understood that nothing should be done which might prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country."[156]

Not all were satisfied with the mandate. Some of the Arabs felt that Britain was violating the McMahon-Hussein Correspondence and the understanding of the Arab Revolt. Some wanted a unification with Syria: In February 1919 several Moslem and Christian groups from Jaffa and Jerusalem met and adopted a platform which endorsed unity with Syria and opposition to Zionism (this is sometimes called the First Palestinian National Congress). A letter was sent to Damascus authorizing Faisal to represent the Arabs of Palestine at the Paris Peace Conference. In May 1919 a Syrian National Congress was held in Damascus, and a Palestinian delegation attended its sessions.[157] In April 1920 violent Arab disturbances against the Jews in Jerusalem occurred which became to be known as the 1920 Palestine riots. The riots followed rising tensions in Arab-Jewish relations over the implications of Zionist immigration. The British military administration's erratic response failed to contain the rioting, which continued for four days. As a result of the events, trust between the British, Jews, and Arabs eroded. One consequence was that the Jewish community increased moves towards an autonomous infrastructure and security apparatus parallel to that of the British administration.

In April 1920 the Allied Supreme Council (the United States, Great Britain, France, Italy and Japan) met at Sanremo and formal decisions were taken on the allocation of mandate territories. The United Kingdom obtained a mandate for Palestine and France obtained a mandate for Syria. The boundaries of the mandates and the conditions under which they were to be held were not decided. The Zionist Organization's representative at Sanremo, Chaim Weizmann, subsequently reported to his colleagues in London:

There are still important details outstanding, such as the actual terms of the mandate and the question of the boundaries in Palestine. There is the delimitation of the boundary between French Syria and Palestine, which will constitute the northern frontier and the eastern line of demarcation, adjoining Arab Syria. The latter is not likely to be fixed until the Emir Feisal attends the Peace Conference, probably in Paris.[158]

The purported objective of the League of Nations Mandate system was to administer parts of the defunct Ottoman Empire, which had been in control of the Middle East since the 16th century, "until such time as they are able to stand alone."[159]

In July 1920, the French drove Faisal bin Husayn from Damascus ending his already negligible control over the region of Transjordan, where local chiefs traditionally resisted any central authority. The sheikhs, who had earlier pledged their loyalty to the Sharif of Mecca, asked the British to undertake the region's administration. Herbert Samuel asked for the extension of the Palestine government's authority to Transjordan, but at meetings in Cairo and Jerusalem between Winston Churchill and Emir Abdullah in March 1921 it was agreed that Abdullah would administer the territory (initially for six months only) on behalf of the Palestine administration. In the summer of 1921 Transjordan was included within the Mandate, but excluded from the provisions for a Jewish National Home.[160] On 24 July 1922 the League of Nations approved the terms of the British Mandate over Palestine and Transjordan. On 16 September the League formally approved a memorandum from Lord Balfour confirming the exemption of Transjordan from the clauses of the mandate concerning the creation of a Jewish national home and from the mandate's responsibility to facilitate Jewish immigration and land settlement.[161] With Transjordan coming under the administration of the British Mandate, the mandate's collective territory became constituted of 23% Palestine and 77% Transjordan. The Mandate for Palestine, while specifying actions in support of Jewish immigration and political status, stated, in Article 25, that in the territory to the east of the Jordan River, Britain could 'postpone or withhold' those articles of the Mandate concerning a Jewish National Home. Transjordan was a very sparsely populated region (especially in comparison with Palestine proper) due to its relatively limited resources and largely desert environment.

In 1923 an agreement between the United Kingdom and France established the border between the British Mandate of Palestine and the French Mandate of Syria. The British handed over the southern Golan Heights to the French in return for the northern Jordan Valley. The border was re-drawn so that both sides of the Jordan River and the whole of the Sea of Galilee, including a 10-metre wide strip along the northeastern shore, were made a part of Palestine[162] with the provisons that Syria have fishing and navigation rights in the Lake.[163]

The Palestine Exploration Fund published surveys and maps of Western Palestine (aka Cisjordan) starting in the mid-19th century. Even before the Mandate came into legal effect in 1923 (text), British terminology sometimes used '"Palestine" for the part west of the Jordan River and "Trans-Jordan" (or Transjordania) for the part east of the Jordan River.[164][165]

The first reference to the Palestinians, without qualifying them as Arabs, is to be found in a document of the Permanent Executive Committee, composed of Muslims and Christians, presenting a series of formal complaints to the British authorities on 26 July 1928.[166]

Infrastructure and development

Between 1922 and 1947, the annual growth rate of the Jewish sector of the economy was 13.2%, mainly due to immigration and foreign capital, while that of the Arab was 6.5%. Per capita, these figures were 4.8% and 3.6% respectively. By 1936, the Jewish sector had eclipsed the Arab one, and Jewish individuals earned 2.6 times as much as Arabs. In terms of human capital, there was a huge difference. For instance, the literacy rates in 1932 were 86% for the Jews against 22% for the Arabs, but Arab literacy was steadily increasing.[167]

Under the British Mandate, the country developed economically and culturally. In 1919 the Jewish community founded a centralized Hebrew school system, and the following year established the Assembly of Representatives, the Jewish National Council and the Histadrut labor federation. The Technion university was founded in 1924, and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in 1925.[168]

As for Arab institutions, the office of “Mufti of Jerusalem”, traditionally limited in authority and geographical scope, was refashioned by the British into that of “Grand Mufti of Palestine”. Furthermore, a Supreme Muslim Council (SMC) was established and given various duties, such as the administration of religious endowments and the appointment of religious judges and local muftis. During the revolt (see below) the Arab Higher Committee was established as the central political organ of the Arab community of Palestine.

During the Mandate period, Many factories were established and roads and railroads were built throughout the country. The Jordan River was harnessed for production of electric power and the Dead Sea was tapped for minerals – potash and bromine.

1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine

Sparked off by the death of Shaykh Izz ad-Din al-Qassam at the hands of the British police near Jenin in November 1935, in the years 1936–1939 the Arabs participated in an uprising and protest against British rule and against mass Jewish immigration. The revolt manifested in a strike and armed insurrection started sporadically, becoming more organized with time. Attacks were mainly directed at British strategic installations such as the Trans Arabian Pipeline (TAP) and railways, and to a lesser extent against Jewish settlements, secluded Jewish neighborhoods in the mixed cities, and Jews, both individually and in groups.

Violence abated for about a year while the Peel Commission deliberated and eventually recommended partition of Palestine. With the rejection of this proposal, the revolt resumed during the autumn of 1937. Violence continued throughout 1938 and eventually petered out in 1939.

The British responded to the violence by greatly expanding their military forces and clamping down on Arab dissent. "Administrative detention" (imprisonment without charges or trial), curfews, and house demolitions were among British practices during this period. More than 120 Arabs were sentenced to death and about 40 hanged. The main Arab leaders were arrested or expelled.

The Haganah (Hebrew for "defense"), an illegal Jewish paramilitary organization, actively supported British efforts to quell the insurgency, which reached 10,000 Arab fighters at their peak during the summer and fall of 1938. Although the British administration didn't officially recognize the Haganah, the British security forces cooperated with it by forming the Jewish Settlement Police and Special Night Squads.[169] A terrorist splinter group of the Haganah, called the Irgun (or Etzel)[170] adopted a policy of violent retaliation against Arabs for attacks on Jews.[171] At a meeting in Alexandria in July 1937 between Jabotinsky and Irgun commander Col. Robert Bitker and chief-of-staff Moshe Rosenberg, the need for indiscriminate retaliation due to the difficulty of limiting operations to only the "guilty" was explained. The Irgun launched attacks against public gathering places such as markets and cafes.[172]

The revolt did not achieve its goals, although it is "credited with signifying the birth of the Arab Palestinian identity.".[173] It is generally credited with forcing the issuance of the White Paper of 1939 which renounced Britain's intent of creating a Jewish National Home in Palestine, as proclaimed in the 1917 Balfour Declaration.

Another outcome of the hostilities was the partial disengagement of the Jewish and Arab economies in Palestine, which were more or less intertwined until that time. For example, whereas the Jewish city of Tel Aviv previously relied on the nearby Arab seaport of Jaffa, hostilities dictated the construction of a separate Jewish-run seaport for Tel-Aviv.

World War II and Palestine

When the Second World War broke out, the Jewish population sided with Britain. David Ben Gurion, head of the Jewish Agency, defined the policy with what became a famous motto: "We will fight the war as if there were no White Paper, and we will fight the White Paper as if there were no war." While this represented the Jewish population as a whole, there were exceptions (see below).

As in most of the Arab world, there was no unanimity amongst the Palestinian Arabs as to their position regarding the combatants in World War II. A number of leaders and public figures saw an Axis victory as the likely outcome and a way of securing Palestine back from the Zionists and the British. Mohammad Amin al-Husayni, Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, spent the rest of the war in Nazi Germany and the occupied areas, in particular encouraging Muslim Bosniaks to join the Waffen SS in German-conquered Bosnia. About 6,000 Palestinian Arabs and 30,000 Palestinian Jews joined the British forces.

On 10 June 1940, Italy declared war on the British Commonwealth and sided with Germany. Within a month, the Italians attacked Palestine from the air, bombing Tel Aviv and Haifa.[174]

In 1942, there was a period of anxiety for the Yishuv, when the forces of German General Erwin Rommel advanced east in North Africa towards the Suez Canal and there was fear that they would conquer Palestine. This period was referred to as the two hundred days of anxiety. This event was the direct cause for the founding, with British support, of the Palmach[175]—a highly-trained regular unit belonging to Haganah (which was mostly made up of reserve troops).

On 3 July 1944, the British government consented to the establishment of a Jewish Brigade with hand-picked Jewish and also non-Jewish senior officers. The brigade fought in Europe, most notably against the Germans in Italy from March 1945 until the end of the war in May 1945. Members of the Brigade played a key role in the Berihah's efforts to help Jews escape Europe for Palestine. Later, veterans of the Jewish Brigade became key participants of the new State of Israel's Israel Defense Force.

Starting in 1939 and throughout the war and the Holocaust, the British reduced the number of Jewish immigrants allowed into Palestine, following the publication of the MacDonald White Paper. Once the 15,000 annual quota was exceeded, Jews fleeing Nazi persecution were placed in detention camps or deported to places such as Mauritius.[176]

In 1944 Menachem Begin assumed the Irgun's leadership, determined to force the British government to remove its troops entirely from Palestine. Citing that the British had reneged on their original promise of the Balfour Declaration, and that the White Paper of 1939 restricting Jewish immigration was an escalation of their pro-Arab policy, he decided to break with the Haganah. Soon after he assumed command, a formal 'Declaration of Revolt' was publicized, and armed attacks against British forces were initiated. Lehi, another splinter group, opposed cessation of operations against the British authorities all along. The Jewish Agency which opposed those actions and the challenge to its role as government in preparation responded with "The Hunting Season" – severe actions against supporters of the Irgun and Lehi, including turning them over to the British.

The country developed economically during the war, with increased industrial and agricultural outputs and the period was considered an `economic Boom'. In terms of Arab-Jewish relations, these were relatively quiet times.[177]

End of the British Mandate 1945–1948

In the years following World War II, Britain's control over Palestine became increasingly tenuous. This was caused by a combination of factors, including:

- World public opinion turned against Britain as a result of the British policy of preventing Holocaust survivors from reaching Palestine, sending them instead to Cyprus internment camps, or even back to Germany, as in the case of Exodus 1947.

- The costs of maintaining an army of over 100,000 men in Palestine weighed heavily on a British economy suffering from post-war depression, and was another cause for British public opinion to demand an end to the Mandate.[178]

- Rapid deterioration due to the actions of the Jewish paramilitary organizations (Hagana, Irgun and Lehi), involving attacks on strategic installations (by all three) as well as on British forces and officials (by the Irgun and Lehi). This caused severe damage to British morale and prestige, as well as increasing opposition to the mandate in Britain itself, public opinion demanding to "bring the boys home".[179]

- US Congress was delaying a loan necessary to prevent British bankruptcy. The delays were in response to the British refusal to fulfill a promise given to Truman that 100,000 Holocaust survivors would be allowed to emigrate to Palestine.

In early 1947 the British Government announced their desire to terminate the Mandate, and asked the United Nations General Assembly to make recommendations regarding the future of the country.[180] The British Administration declined to accept the responsibility for implementing any solution that wasn't acceptable to both the Jewish and the Arab communities, or to allow other authorities to take over responsibility for public security prior to the termination of its mandate on 15 May 1948.[181]

UN partition and the 1948 Israeli-Arab War

|

On 29 November 1947, the United Nations General Assembly voted 33 to 13 with 10 abstentions, in favour of a plan to partition the territory into separate Jewish and Arab states, under economic union, with the Greater Jerusalem area (encompassing Bethlehem) coming under international control. Zionist leaders (including the Jewish Agency), accepted the plan, while Palestinian Arab leaders rejected it and all independent Muslim and Arab states voted against it.[182][183][184] Almost immediately, sectarian violence erupted and spread, killing hundreds of Arabs, Jews and British over the ensuing months.

The rapid evolution of events precipitated into a Civil War. Arab volunteers of the Arab Liberation Army entered Palestine to fight with the Palestinians, but the April-May offensive of Yishuv forces crushed the Arabs and Arab Palestinian society collapsed. Some 300,000 to 350,000 Palestinians caught up in the turmoil fled or were driven from their homes.

On 14 May, the Jewish Agency declared the independence of the state of Israel. The neighbouring Arab state intervened to prevent the partition and support the Palestinian Arab population. While Transjordan took control of territory designated for the future Arab State, Syrian, Iraqi and Egyptian expeditionary forces attacked Israel without success. The most intensive battles were waged between the Jordanian and Israeli forces over the control of Jerusalem.

On June 11, a truce was accepted by all parties. Israel used the lull to undertake a large-scale reinforcement of its army. In a series of military operations, it then conquered the whole of the Galilee region, both the Lydda and Ramle areas, and the Negev. It also managed to secure, in the Battles of Latrun, a road linking Jerusalem to Israel. In this phase, 350,000 more Arab Palestinians fled or were expelled from the conquered areas.

During the first 6 months of 1949, negotiations between the belligerents came to terms over armistice lines that delimited Israel's borders. On the other side, no Palestinian Arab state was founded: Jordan annexed the Arab territories of the Mandatory regions of Samaria and Judea (today known as the West Bank), as well as East Jerusalem, while the Gaza strip came under Egyptian administration.

The New Historians, like Avi Shlaim, hold that there was an unwritten secret agreement between King Abdullah of Transjordan and Israeli authorities to partition the territory between themselves, and that this translated into each side limiting their objectives and exercising mutual restraint during the 1948 war.[185]

1948 to present

| Arab-Israeli conflict | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Israel and members of the Arab League |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

Arab nations |

Israel |

||||||

|

Arab-Israeli conflict series

Participants

Israeli-Palestinian conflict · Israel-Lebanon conflict · Arab League · Soviet Union / Russia · Israel, Palestinians and the United Nations · Iran-Israel relations · Israel-United States relations · Boycotts of Israel Peace treaties and proposals

Israel-Egypt · Israel-Jordan |

|||||||

On the same day that the State of Israel was announced, the Arab League announced that it would set up a single Arab civil administration throughout Palestine,[186][187] and launched an attack on the new Israeli state. The All-Palestine government was declared in Gaza on 1 October 1948,[188] partly as an Arab League move to limit the influence of Transjordan over the Palestinian issue. The former mufti of Jerusalem, Haj Amin al-Husseini, was appointed as president. The government was recognised by Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, and Yemen, but not by Transjordan (later known as Jordan) or any non-Arab country. It was little more than an Egyptian protectorate and had negligible influence or funding. Following the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, the area allocated to the Palestinian Arabs and the international zone of Jerusalem were occupied by Israel and the neighboring Arab states in accordance with the terms of the 1949 Armistice Agreements. Palestinian Arabs living in the Gaza Strip or Egypt were issued with All-Palestine passports until 1959, when Gamal Abdul Nasser, president of Egypt, issued a decree that annulled the All-Palestine government.

In addition to the UN-partitioned area allotted to the Jewish state, Israel captured and incorporated a further 26% of the Mandate territory (namely of the territory to the west of the Jordan river). Jordan captured and annexed about 21% of the Mandate territory, which it referred to as the West Bank (to differentiate it from the newly-named East Bank – the original Transjordan). Jerusalem was divided, with Jordan taking the eastern parts, including the Old City, and Israel taking the western parts. The Gaza Strip was captured by Egypt. In addition, Syria held on to small slivers of Mandate territory to the south and east of the Sea of Galilee, which had been allocated in the UN partition plan to the Jewish state.

For a description of the massive population movements, Arab and Jewish, at the time of the 1948 war and over the following decades, see Palestinian exodus and Jewish exodus from Arab lands.

In the course of the Six Day War in June 1967, Israel captured the West Bank (including East Jerusalem) from Jordan and the Gaza Strip from Egypt.

From the 1960s onward, the term "Palestine" was regularly used in political contexts. The Palestine Liberation Organization has enjoyed status as a non-member observer at the United Nations since 1974, and continues to represent "Palestine" there.[189] According to the CIA World Factbook,[190][191][192] of the ten million people living between Jordan and the Mediterranean Sea, about five million (49%) identify as Palestinian, Arab, Bedouin and/or Druze. One million of those are citizens of Israel. The other four million are residents of the West Bank and Gaza, which are under the jurisdiction of the Palestinian National Authority, which was formed in 1994, pursuant to the Oslo Accords. As of July 2009, approximately 305,000 Israelis live in the 121 officially-recognised settlements in the West Bank.[193] The 2.4 million West Bank Palestinians (according to Palestinian evaluations) live primarily in four blocs centered in Hebron, Ramallah, Nablus, and Jericho. In 2005, Israel withdrew its army and all the Israeli settlers were evacuated from the Gaza Strip, in keeping with Ariel Sharon's plan for unilateral disengagement, and control over the area was transferred to the Palestinian Authority. However, due to the Hamas-Fatah conflict, the Gaza Strip has been in control of Hamas since 2006.

Demographics

Early demographics

Estimating the population of Palestine in antiquity relies on two methods – censuses and writings made at the times, and the scientific method based on excavations and statistical methods that consider the number of settlements at the particular age, area of each settlement, density factor for each settlement.

According to Magen Broshi, an Israeli archaeologist "... the population of Palestine in antiquity did not exceed a million persons. It can also be shown, moreover, that this was more or less the size of the population in the peak period—the late Byzantine period, around AD 600"[194] Similarly, a study by Yigal Shiloh of The Hebrew University suggests that the population of Palestine in the Iron Age could have never exceeded a million. He writes: "... the population of the country in the Roman-Byzantine period greatly exceeded that in the Iron Age...If we accept Broshi's population estimates, which appear to be confirmed by the results of recent research, it follows that the estimates for the population during the Iron Age must be set at a lower figure."[195]

Demographics in the late Ottoman and British Mandate periods

In the middle of the first century of the Ottoman rule, i.e. 1550 CE, Bernard Lewis in a study of Ottoman registers of the early Ottoman Rule of Palestine reports:[196]

From the mass of detail in the registers, it is possible to extract something like a general picture of the economic life of the country in that period. Out of a total population of about 300,000 souls, between a fifth and a quarter lived in the six towns of Jerusalem, Gaza, Safed, Nablus, Ramle, and Hebron. The remainder consisted mainly of peasants, living in villages of varying size, and engaged in agriculture. Their main food-crops were wheat and barley in that order, supplemented by leguminous pulses, olives, fruit, and vegetables. In and around most of the towns there was a considerable number of vineyards, orchards, and vegetable gardens.

By Volney's estimates in 1785, there were no more than 200,000 people in the country.[197] According to Alexander Scholch, the population of Palestine in 1850 had about 350,000 inhabitants, 30% of whom lived in 13 towns; roughly 85% were Muslims, 11% were Christians and 4% Jews[198]

According to Ottoman statistics studied by Justin McCarthy,[199] the population of Palestine in the early 19th century was 350,000, in 1860 it was 411,000 and in 1900 about 600,000 of which 94% were Arabs. In 1914 Palestine had a population of 657,000 Muslim Arabs, 81,000 Christian Arabs, and 59,000 Jews.[200] McCarthy estimates the non-Jewish population of Palestine at 452,789 in 1882, 737,389 in 1914, 725,507 in 1922, 880,746 in 1931 and 1,339,763 in 1946.[201]

Official reports

In 1920, the League of Nations' Interim Report on the Civil Administration of Palestine stated that there were 700,000 people living in Palestine:

Of these 235,000 live in the larger towns, 465,000 in the smaller towns and villages. Four-fifths of the whole population are Moslems. A small proportion of these are Bedouin Arabs; the remainder, although they speak Arabic and are termed Arabs, are largely of mixed race. Some 77,000 of the population are Christians, in large majority belonging to the Orthodox Church, and speaking Arabic. The minority are members of the Latin or of the Uniate Greek Catholic Church, or—a small number—are Protestants. The Jewish element of the population numbers 76,000. Almost all have entered Palestine during the last 40 years. Prior to 1850 there were in the country only a handful of Jews. In the following 30 years a few hundreds came to Palestine. Most of them were animated by religious motives; they came to pray and to die in the Holy Land, and to be buried in its soil. After the persecutions in Russia forty years ago, the movement of the Jews to Palestine assumed larger proportions.[202]

By 1948, the population had risen to 1,900,000, of whom 68% were Arabs, and 32% were Jews (UNSCOP report, including bedouin).

Current demographics

According to Israel's Central Bureau of Statistics, as of May 2006, of Israel's 7 million people, 77% were Jews, 18.5% Arabs, and 4.3% "others".[203] Among Jews, 68% were Sabras (Israeli-born), mostly second- or third-generation Israelis, and the rest are olim — 22% from Europe and the Americas, and 10% from Asia and Africa, including the Arab countries.[204]

According to Palestinian evaluations, The West Bank is inhabited by approximately 2.4 million Palestinians and the Gaza Strip by another 1.4 million. According to a study presented at The Sixth Herzliya Conference on The Balance of Israel's National Security[205] there are 1.4 million Palestinians in the West Bank. This study was criticised by demographer Sergio DellaPergola, who estimated 3.33 million Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza Strip combined at the end of 2005.[206]

According to these Israeli and Palestinian estimates, the population in Israel and the Palestinian Territories stands at 9.8–10.8 million.

Jordan has a population of around 6,000,000 (2007 estimate).[207][208] Palestinians constitute approximately half of this number.[209]

See also

- Israeli-Palestinian conflict

- Names of the Levant

- Outline of the Palestinian territories

- Place names of Palestine

- Province of Judah ("Yehud Medinata")

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "The Palestine Exploration Fund". The Palestine Exploration Fund. http://www.pef.org.uk/oldsite/Paldef.htm. Retrieved 2008-04-04.

- ↑ ""Legal Consequence of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory"". Icj-cij.org. 2004-07-09. http://www.icj-cij.org/docket/index.php?pr=71&code=mwp&p1=3&p2=4&p3=6&case=131&k=5a. Retrieved 2010-08-24.

- ↑ Boundaries Delimitation: Palestine and Trans-Jordan, Yitzhak Gil-Har, Middle Eastern Studies, Vol. 36, No. 1 (Jan., 2000), pp. 68-81: "Palestine and Transjordan emerged as states; This was in consequence of British War commitments to its allies during the First World War.

- ↑ Marjorie M. Whiteman, Digest of International Law, vol. 1, US State Department (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1963) pp 650-652

- ↑ Forji Amin George (June 2004). "Is Palestine a State?". Expert Law. http://www.expertlaw.com/library/international_law/palestine.html. Retrieved 2008-04-04.

- ↑ Fahlbasch and Bromiley, 2005, p. 14.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 Sharon, 1988, p. 4.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Room, 1997, p. 285.

- ↑ Greek Παλαιστινη from Φυλιστινος/Φυλιστιειμ, see e.g. Josephus, Antiquities I.136; cf. First Book of Moses (Genesis) X.13.